Legal market trends: here’s an introduction to some of the main issues on the minds of today’s lawyers.

Covid-19 and the legal profession

For the legal profession or otherwise, the Covid-19 crisis has redrawn the way we work. And if it’s taught businesses one thing, it’s that they need to be nimble. In an industry better known for honouring traditional working practices, relocating inner-City offices into the homes of tens or hundreds of employees was previously unthinkable for many law firms, and even more so for the Bar. Now, home working and virtual meetings characterise the contemporary legal landscape. Perks abound from the new normal, from greater autonomy and flexibility around hours, to saving on the daily commute and sandwiches in Pret.

But for lawyers in the infancy of their practice, there have also been challenges. Working from home simply doesn’t replicate office life. It’s more difficult to observe senior colleagues, for example, or to quickly run a question by a supervisor. To straddle this gulf post-pandemic, most firms are beginning to introduce hybrid systems whereby employees split their working week between home and the office.

The virtual shift has had additional impacts at the Bar. 85% of cases heard in business courts have gone ahead virtually, according to statistics from the Law Society, and the Supreme Court heard its first ever virtual hearing in March 2020. But while virtual hearings have coloured the quotidian, a report by the Bar Council notes that 80% of barristers do not feel that people are currently able to access an acceptable level of justice. The report also shows just how hard publicly funded barristers have been hit by court closures: 38% of criminal barristers say they are uncertain whether they will still be practicing law by the end of 2021.

Some experts warn the current backlog of cases will take at least a decade to clear. For example, as of June 2021, there was a record backlog of 60,000 cases in the Crown Court. On the other hand, figures reported in the legal press from the Rolls Building showed that 50% of cases in the Chancery Division lasted less than an hour, while 70% clocked in at under two. The speedy resolution of these cases led to praise being bestowed on virtual hearings as a way to increase efficiency and set up the commercial courts for the future. The Law Society subsequently reported that the commercial courts had almost no backlog of cases and that levels of activity were comparable to previous years. While it looks unlikely that virtual hearings will have the same dominance once the pandemic is over, you can confidently expect the business and property courts to make more use of them and incorporate them in a hybrid approach to processing cases in the future.

While firms precautionarily responded to the pandemic with delayed partner promotions, slashed salaries, and amendments to trainee intake processes, things have largely returned to normal. In fact, many firms have recorded healthy revenue growth and the ongoing salary war in the City has pushed NQ salaries to an all-time high.

Unsurprisingly, insolvency and restructuring enquiries have been a major focus area for law firms over the last 18 months, as have questions from clients regarding furlough and employment. Companies are also turning to law firms for advice on their obligations regarding contingency plans and disclosures to shareholders. Disputes over the invocation of ‘force majeure’ clauses – whereby contractual obligations remain unfulfilled due to unforeseen circumstances – are also expected to mar the road ahead. Similarly, insurance claims will continue keeping firms busy; a recent High Court ruling found that around 370,000 small companies will receive pay-outs after being forced to close during the pandemic.

Brexit

The EU–UK Trade and Cooperation Agreement came into effect on 1 January 2021 when the Brexit transition period ended. For businesses that witnessed years of protracted negotiations and were operating on the premise that a no-deal scenario was the most likely outcome, the agreement came as relief. However, the deal was far from comprehensive, leaving many sectors and industries facing significant challenges moving forward. For example, financial services firms have lost their ‘passporting rights,’ which in the past allowed them to sell their services into the EU without friction.

“The need to work with EU qualified lawyers is crucial.”

Mickaël Laurans, Head of International at The Law Society elaborates on some of the winners and losers of the deal: “Firms advising on heavily regulated sectors like chemicals, pharma and financial services will be affected when there is an EU law element in the advice and they come into the issue of professional privilege. The need to work with EU qualified lawyers is crucial.” Alternatively, Laurans highlights that “there has been explosive growth in the area of international trade law advice in the UK. Where previously trade lawyers were traditionally based in Geneva, Brussels and DC, London has increasingly become a centre of activity as clients seek counsel on trade issues.”

At an operational level, many firms have been busy restructuring themselves in ways that will allow them to continue to best serve their clients. As many UK-qualified lawyers lost the formal right available under EU membership to advise on host state law and EU law, many have requalified in other European countries. The reputation of the UK’s commercial courts will ensure that London remains a key legal and economic hub. However, questions remain over the recognition and enforcement of UK judgment into the EU. Read more about the impact of Brexit here.

New technologies

Artificial intelligence is no longer a science fiction pipe dream – the SRA suggests that AI has the potential to increase business efficiency for both law firms and their clients. Reports estimate that it could create 14.9 million new jobs in the UK by 2027 and add £630 billion to the economy by 2035. Clearly, now is as good a time as any to jump on board the tech bandwagon. Top firms are definitely feeling the pressure to invest in AI. There appears to be a race on among the bigger firms to build homegrown AI capability, and they're not just competing with other law firms, but against new emerging Alternative Legal Services Providers (ALSPs) and against their own big clients, for whom the cost saving potential with AI could be massive.

We asked a City firm partner for the tech tea: “AI will help lawyers perform their tasks, but it won’t be replacing them. If a client comes to us and needs work on a restructuring matter or a corporate transaction, the human part of our service is still critical in finding solutions that work for that particular client in that instance. Firms need to look at the individual project and implement AI on a case-by-case basis.” One of the biggest potential advantages of AI is its ability to quickly and efficiently complete the menial tasks which many trainees grow to loathe, potentially freeing them up to get more useful experience during their training contract.

Climate and sustainability

Perhaps the single largest threat hovering over the legal industry – and the Earth generally – is the burgeoning climate crisis. Failure to tackle global warming will reshape the nature of work in various practice areas within the law. Climate change litigation will increasingly affect both public and private law; traditional oil and gas work will shift in importance as more sustainable energy resources are sought out, a trend that’s already underway now; ecocide is discussed as a means to legally render companies culpable for damages done to ecosystems; and new structures emerge – such as the Nansen Initiative – which seek to provide legal protection for refugees fleeing inhospitable conditions and disasters caused by the changing climate.

As the law becomes increasingly globalised, so the legal industry must become more conscious of the potential effects of climate change on a planet-wide scale. Law firms are also having to adapt on a more basic level, moving towards paperless offices and thinking of new ways to make their everyday practice more sustainable. The biggest changes will of course take place on a society-challenging scale as governments adapt to the impending disaster through legislation. Lawyers will queue up to tell you that change means more work for them, and a changing climate is no exception.

The SQE

Here’s another topic with major consequences that’s unquestionably a result of human activity. The Solicitor’s Qualifying Exam has been officially rolled out and is one of the biggest shakeups to the legal profession in recent history. No longer will aspiring lawyers need to claw through the LPC (and GDL if they’re a non-law grad) before tackling a two-year training contract. In future, any Tom, Dick or Harriet can pass two tests and do 24 months of legal work experience, potentially with multiple different employers, and then qualify as a solicitor. However, for those that have already started their law degree or an exempting law degree, you still have the option of qualifying in the same way as before (through the LPC course). Many law firms and law schools are still in the process of working out their response to the rollout, though it is expected that most firms will continue to require candidates to complete something akin to the current model of a two-year training contract.

While the SRA argues that the plans will help speed up the diversification of the legal progression, firms have argued that candidates may be able to slip through the process without the skills necessary for actually doing the job of a solicitor. There have also been concerns that proposed plans to reduce costs for prospective solicitors may come to naught, as they’ll almost certainly have to complete an SQE prep course if they have any hopes of passing the exam; and that unprepared applicants may show up to the tests having already forked out a wad of cash, with no real prospect of securing a qualification.

Lawyers’ educational backgrounds

Calculators at the ready, it’s stats time. In 2021, we conducted a study of over 2,000 trainees from across the country; looking back over the past nine years we examined the trends of where trainees at top firms did their undergraduate degrees. We found that law firms’ appetite for Oxbridge and Russell Group students has remained pretty much constant – those universities consistently supplied just over 75% of trainees between 2016 and 2021.

There have been some encouraging changes, however. In summer 2020, our research of the educational backgrounds of trainees at the top law firms revealed that just 44% of our respondents attended a state school in the UK for secondary education; across England as a whole, around 85% of pupils attend a state-funded secondary school. In 2021, this number increased by over 10% suggesting attempts by firms to diversify their intakes are paying off. However, there remains an overall bias towards the privately educated in the junior ranks of the legal industry. Law firms are continuing to take steps to address this – particularly through partnerships with RARE Recruitment – but it’s clear there’s still a long way to go.

…a continued overall bias towards the privately educated in the junior ranks of the legal industry.

Diversity and inclusion

While we’re on the subject of diversity, it’s worth celebrating recent success while also focusing on the continued challenges faced by diverse lawyers. Our 2021 review of diversity in the law found that the market-wide percentages of female trainees, associates and partners have all increased (albeit by a little) in the past six years; that regional and niche firms are surprisingly leading the charge on recruiting ethnic minority trainees; and that among the top-performing firms on LGBTQ+ diversity, numbers were heading on the right direction at every career level. That doesn’t mean job-done by any stretch of the imagination, and law firms continue to be more white, male and cishet and less likely to have a disability than the UK population at large (especially at the most senior and partner levels).

We also surveyed trainees on how they felt their own firms were doing on diversity and inclusion. On average, respondents at City firms rated their employers better at recruiting diverse candidates and providing inclusivity training, compared to those trainees at firms based outside London. Men were also consistently scored firms’ efforts higher than women.

Legal aid

Over the last decade, annual legal aid expenditure in the UK has fallen by £950 million, or 38%, in real terms. The result is that half of all not-for-profit legal advice services and law centres in Wales and England have closed since 2013. In July 2021, the House of Commons Justice Select Committee released a damning 82-page report outlining the need for robust and urgent reform to rescue the legal aid sector. The committee sought to identify the ‘core problems’ of the current legal aid framework and provide solutions to improve its long-term future. It found that the unsustainability of both criminal and civil legal aid warrants immediate action, stressing the ‘urgent need to overhaul’ the current criminal legal aid system, as well as finding a ‘strong case’ for making fundamental changes to civil legal aid.

“There’s a huge focus on pro bono work here.”

As the funding in the public sector has collapsed, the private sector (i.e. law firms) has stepped up its pro bono offering to fill the gap. However, this goes nowhere near far enough in addressing the crisis. Whether this is a response to government cuts; or due to the greater importance placed on pro bono work by the many US law firms entering the UK market; or simply an increasing level of corporate social responsibility among millennials, is hard to tell. Whatever the reason, pro bono is gaining traction and many firms have forged relationships with organisations such as community legal advice centres. A trainee at one firm noted that “there’s a huge focus on pro bono work here. We’re really encouraged to be involved, from the top down.” One US firm requires all its lawyers, including in the UK, to complete a certain number of pro bono hours a year in order to be eligible for their bonus. Kingsley Napley mandates its trainees do some pro bono in order to fulfil contentious training requirements for the SRA. Ashurst offers a dedicated six-month pro bono seat. You can read more about the future of legal aid here.

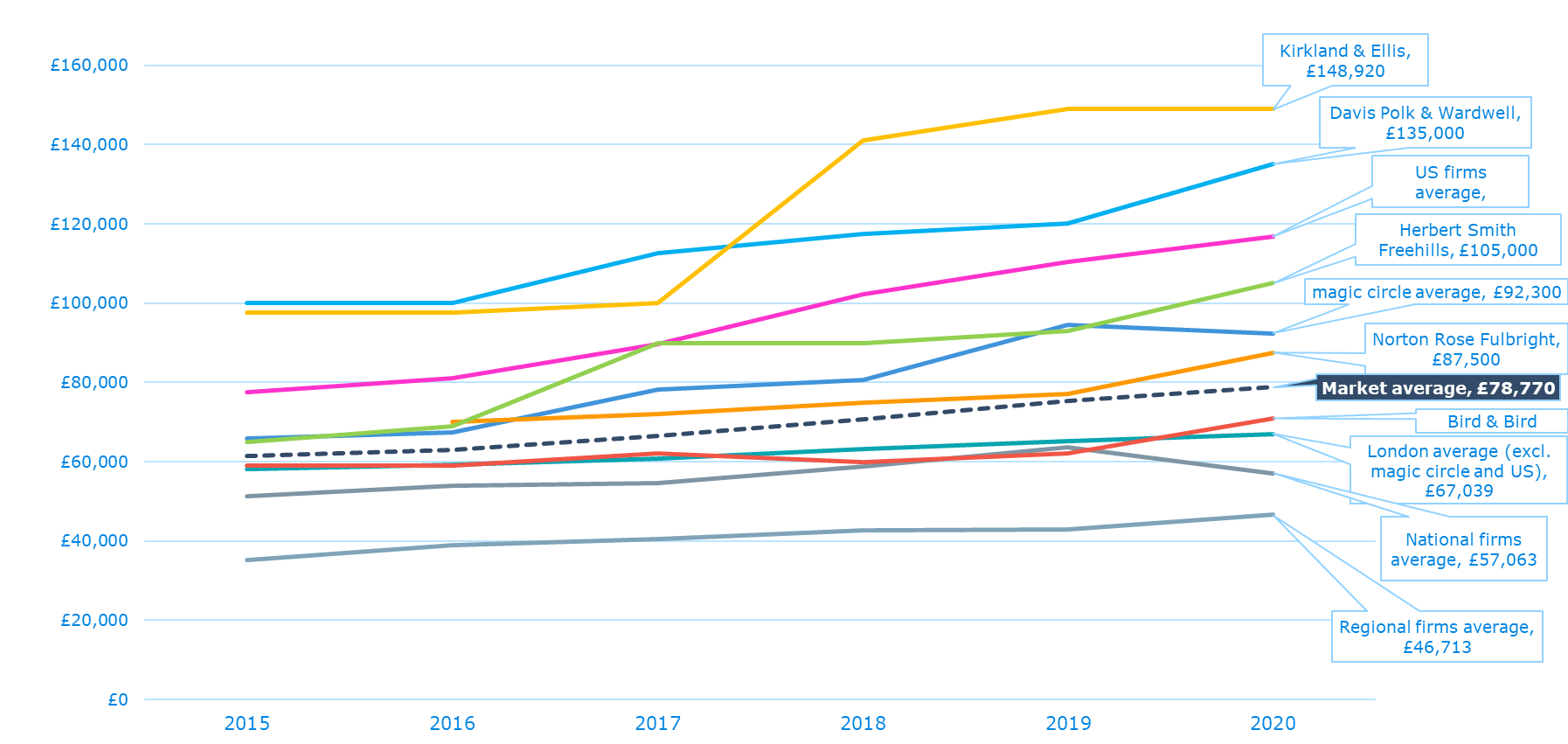

Salary wars

In recent years, the Transatlantic titans have had a major disruptive effect on salaries in the London legal universe, setting the market standard for associates closer to mind-boggling levels that are par the course in New York. In response to the vanguard action by US firms, the magic circle firms over the course of 2021 have now upped their base NQ pay to £100,000. NQs at other big City players like Herbert Smith Freehills can now also expect a six-figure compensation package. However, with some firms there’s a degree of smoke and mirrors going on here, as the ‘total compensation’ offered may include a discretionary bonus.

US firms are still undeniably leading the charge regardless. Latham & Watkins and Kirkland & Ellis NQs top the tree as the highest-paid in the city – salaries at these firms are pegged to the dollar and start at an eye-watering $205,000. Vinson & Elkins also pays a comparable £153,400 upon qualification. Such figures send a message about the sorts of hours associates are expected to work (spoiler alert: they’re long). Read more about how salaries have changes over the past decade here.

The Big Four

A new challenge to the legal elite’s supremacy has emerged over the last few years. PwC employs 3,600 lawyers worldwide – that’s more than Allen & Overy, Kirkland or Skadden. Deloitte employs 2,400 lawyers; EY and KPMG both hire lawyers in over 70 jurisdictions. These are not law firms, but the ‘Big Four’: professional services bruisers best known for accounting, referred to as ‘bean counters’ by Private Eye in its investigations of them. Ever since the 2007 Legal Services Act liberalised the market, these four have lingered as a considerable threat to the current status quo (alongside the charge of so-called Alternative Legal Services Providers like Axiom).

These four have lingered as a considerable threat to the current status quo.

Think about it: if a huge company can use a one-stop-shop to get its accounts sorted, deals closed, cases settled and generally receive slick multi-disciplinary business advice, that has to be an attractive proposition. The Big Four have other things going for them too: their global footprint leaves most law firms eating dust. It’s the same with tech: many lawyers still contend with outdated IT systems, and their firms’ use of AI only scratches the surface of what’s available. It’s different for the Big Four, who are already putting legal tech at the forefront of their offering. But there is one huge factor standing in their way: the specialist expertise of law firms. Alternative Legal Service Providers gain much of their work by being more cost efficient on the more pedestrian legal tasks and for the most high-stakes matters, the best law firms still have a clear edge.

Freelance lawyers

Some lawyers may not need to join a firm at all, following what’s been described as the potential ‘uberisation’ of legal services. No, lawyers aren’t going to start driving drunken partygoers around – the SRA has confirmed that as of November 2019, solicitors are able to give legal advice on a freelance basis. They won’t have to register as a sole practitioner, won’t have to practise as part of a wider firm and won’t have to work as in-house counsel. Instead, they will be allowed to generate their own work and be subject to less rigorous regulation than ‘normal’ solicitors.

The plan has been met with dismay by many who’ve cited potential problems with regulation – the Law Society described the idea of freelance solicitors as a ‘Wild West’ model. Although anyone working ‘freelance’ will have to buy professional indemnity insurance, it’s true that they will not need the same level of cover that is required by lawyers practicing in a firm or in-house. They will have to explain the limits of their insurance to clients, but critics believe that most won’t fully understand the differences. Over to the case for the defence – one of the cited benefits of the change is the potential to broaden diversity in the legal profession by allowing prospective lawyers from non-traditional backgrounds to carve their own path.

Treat this info as a starting point for further research on the Chambers Student website and beyond. Take what you learn and use it when making applications – some of these topics might well come up at interview.