Over seven years of recruitment cycles, we've tracked how law firms have recruited and promoted women.

- Some progress is happening – but slowly

- We reveal a new, unreported gender pay-gap across the industry

- Firms struggle to make long-term careers attractive to women

- Law firm retention performance has remained flat over six years

16 Feb 2021 | Olivia O'Driscoll and Antony Cooke

If law firm diversity initiatives have been commonplace – and well resourced – for years, why is it that women still earn much less, leave firms quicker, and are far less likely to make partner than men?

We’ve tracked the number of women hired, retained and promoted in law firms for seven years. Here we analyse the big trends we’ve seen from 2014 to 2021, and explore the reasons why we’re seeing slow progress in some areas, but an industry falling short in most.

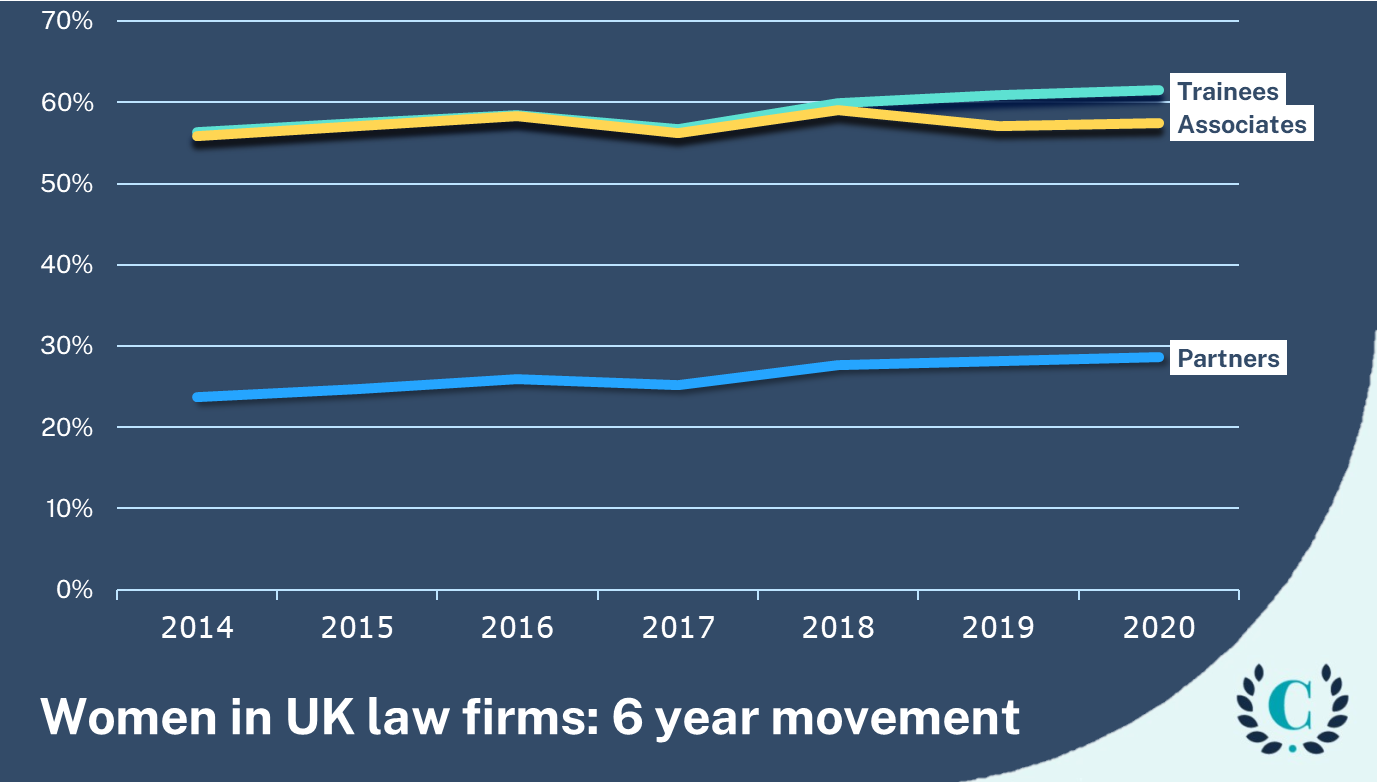

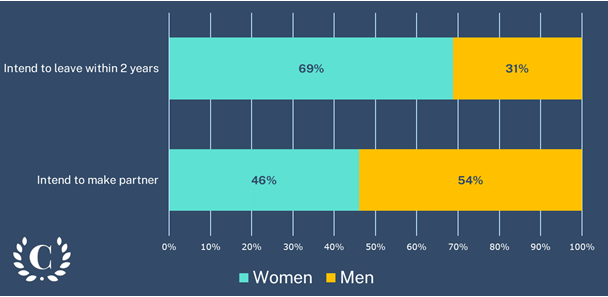

The numbers below show gradual increase at all levels: partners and trainees have grown by 5% over six years; associates by 2%.

At first glance you might consider the trainee figures above to be a sign of success for women, with men representing less than half the successful candidates. But throughout this period, graduates of law school have been c.63% female; we’re still not there at trainee level, and entry-level recruitment is a far easier problem to solve than retention and promotion.

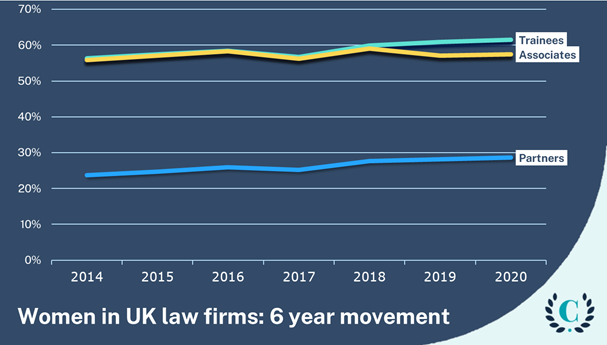

Hiring more women is one way to improve diversity, but as these graphs show, keeping women at the firm is the far bigger challenge. The ‘retention gap’ below measures the percentage difference between female partners and female trainees. This is a blunt tool for measurement – we’re not tracking hiring v. promotion figures – but it’s telling nonetheless. We learn that, although we see incremental improvement in numbers, the legal market hasn’t improved its performance in retention over six years: this has remained flat. Representation of women at the top may have improved by 5%, but flat retention performance implies firms are doing little to change the working cultures that cause attrition, and are instead solving the diversity problem by hiring more women at graduate level.

Retaining talent

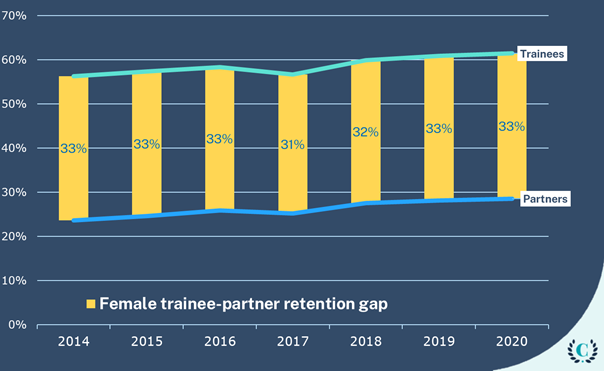

In our research this year we found the problems with commitment to the firm begin as early as at trainee level. We asked 2,655 trainees: 'Assuming you are kept on at qualification, how long will you stay at your firm?' Here we compare the two extreme responses: 'intend to leave within two years'; 'intend to make partner'.

Women are more likely to intend to leave their firm within the first two years; men are more likely to head for partnership. Two troubling issues arise here: why are women so much more likely to want to leave? What’s standing in the way of their ambition to make partner?

The answer is complicated of course – the reasons are vast and subjective. But there are three common trends across the profession reinforcing this problem that we should highlight:

- Lack of role models

If the trainee doesn’t identify personally with leadership – if there’s an identity distance – they won’t feel as entitled to the leadership roles as those who do not feel that separation as palpably. This creates a barrier in women’s ambition and entitlement. And for those who do stay and move up, impostor syndrome becomes a risk, creating a variety of adverse effects. So the smarter option for so many women is to take from the firm what they need on their CVs and jump ship to somewhere more progressive.

- Outdated economy

Law firms are high-pressured places, where personal ownership of cases and clients, and portfolio building are fundamental to career progression. It’s a traditional and inflexible model. The legal profession has no adequate response to the disproportionate burden of family life that continues to be placed on women. The law has to date failed to adjust its economic model to suit contemporary attitudes and aspirations. Attempts to share workload over larger and more flexible staff numbers is met with stiff opposition, mainly because of lawyer earnings.

- Implicit bias

This is the third big problem in retention. Implicit bias in law firms plays out in very subtle preferential treatment given to one type of person over another – so subtle a lot of leaders and managers don't realise when they're doing it. The law is a profession based on relationships, so it happens very frequently, but in small doses each time. These interactions and minor injustices stack up, and after a hundred instances of subtle bias, the career opportunities for a women and a man have materially diverged. Basic D&I training is available at all firms, but the subtleties of implicit bias mean most D&I work fails to keep it in check, and influences beyond the workplace reinforce biases and undo a lot of good work.

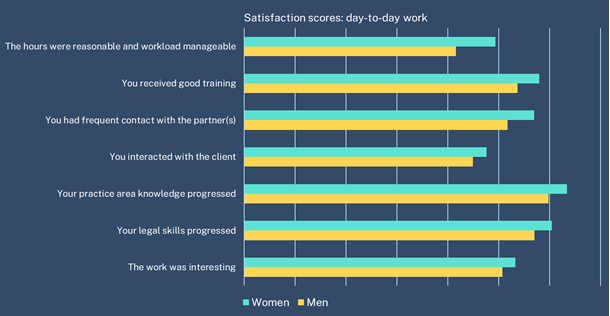

In 2020 we and asked trainees how satisfied they were with various aspects of their law firm life. We then compared the responses from men and women. Here we're looking at seat-by-seat satisfaction experienced by trainees. We see women are marginally happier than men in all their day-to-day experiences and interactions.

From this we learn that women find their day-to-day jobs slightly more rewarding than men. That, despite this, they’re choosing to leave earlier than men illustrates how influential those three factors – role models; outdated economy; implicit bias – are in determining women’s career decisions. What we may be seeing here is evidence that law firms are channelling their energy towards women to make sure their experience is positive – to see these efforts result in high departure numbers must be a frustration to firms. It could also be a sign that women are more inclined to rate their firms more positively than men!

Push and pull factors

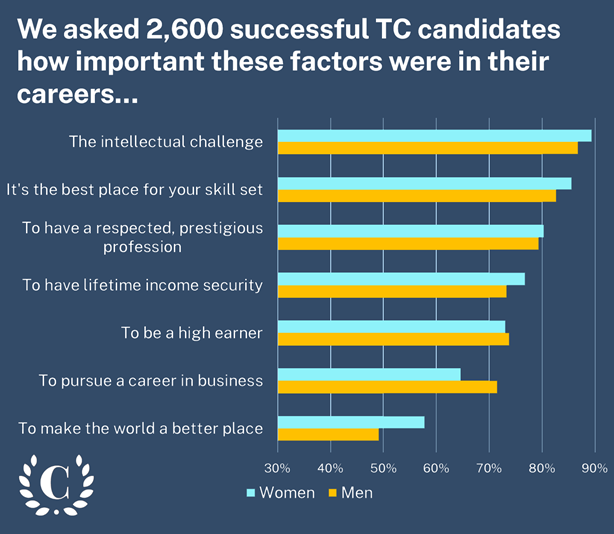

For all the barriers put in place, there is also an element self-selection, as we see below.

In our research across the world, we find men to be more motivated by commercial law and women more likely to want to use their education to make the world a better place. This means we see fewer men pursuing careers in practice areas where clients are individuals rather than companies – employment, crime, family, private client, human rights, immigration, personal injury. These practice areas also coincide with lower earnings; the practice areas more attractive to men also pay more.

A new type of gender pay gap

These findings above point to a new type of gender pay-gap in the law: one that goes undetected by the annual internal reports. The firms paying the highest NQ salaries hire more men; those paying the lower salaries hire more women. The divide between earnings only becomes more pronounced as lawyers progress to partnership, giving men a heavily skewed share of the wealth.

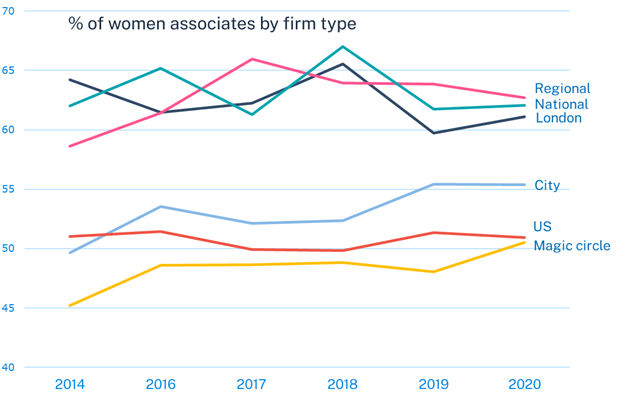

Above we mentioned the question of self-selection – there are push and pull-factors in every decision, but to focus on that does little to solve this divide in opportunity. The graph below illustrates further why we see this divide in earnings. We tracked the percentage of female associates over seven years of recruitment cycles. Two clear groups are forming between firms paying elite salaries and the rest. Some incremental improvement is happening in the City, but it’s still nowhere close to the rest of the market.

The best bet to make partner

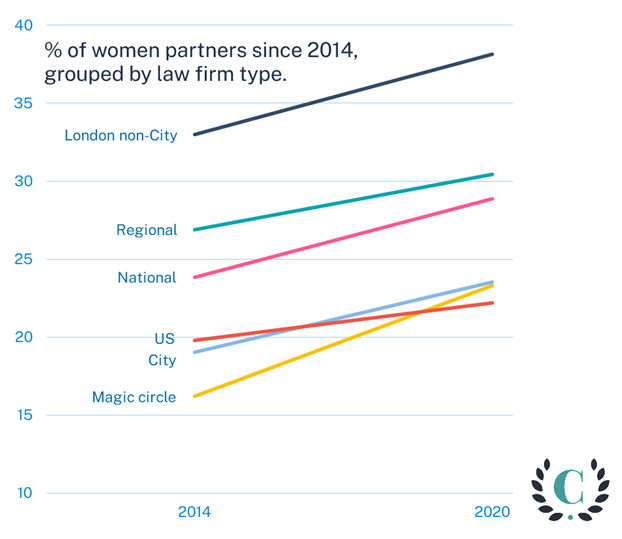

If this data is going to help anyone, we should at least show women entering the legal profession the most likely path to the top. Below we split out the UK market by law firm type, showing which firms are best at promoting women to partner: their performance trajectories shown from 2014 to 2020.

Why the London non-City firms outstrip every other firm is interesting. Firstly, the likes of Kingsley Napley, Farrer, Peters & Peters and Leigh Day have women as managing partners. Female leadership has a profound impact on promotion and retention.

Secondly, the practice areas these firms specialise in attract more women than men, so the role models are there to retain talent for the longer term and encourage ambition.

The City stands out here for its weak performance. Two of the three influences we noted above – lack of role models; inflexible economy – are at their strongest in the City firms. Conversely, the City firms are perhaps the most aware of the problem, and divert a much larger portion of budget into addressing it through initiatives, mentorship and affinity groups. Some firms, such as Travers Smith, have audited their internal culture and built good D&I practices into whole-firm culture. And as we see here, the progress of the magic circle should be noted – their efforts in promoting BAME lawyers has seen particular success.

A glimmer of hope might come from the permanent changes brought by lockdown life – at least on the topic of mixing parenting and the law. Flexible working is no longer the career compromise that it was. Additionally, legal tech’s rise to power threatens to disrupt the rigid partnership pipeline. Generous lawyer earnings will mean firms will probably respond too slowly to this threat, lacking the immediate financial incentive to change. But change will happen, and looking after lawyers’ quality of life throughout that revolution will be a prominent discussion point.

For both men and women, this information is at once a warning – a call to be vigilant of complacent and outdated cultures as you research your law firms – and an encouragement as you enter this fast-changing profession: this era will reward anyone who adopts inclusive behaviours.

Our survey

For seven years we have tracked UK law firms on their key diversity metrics. On gender we collect figures on partners, associate and trainees. The survey covers 147 law firms in the UK, representing the more competitive half of the legal industry.

For seven years we have tracked UK law firms on their key diversity metrics. On gender we collect figures on partners, associate and trainees. The survey covers 147 law firms in the UK, representing the more competitive half of the legal industry.

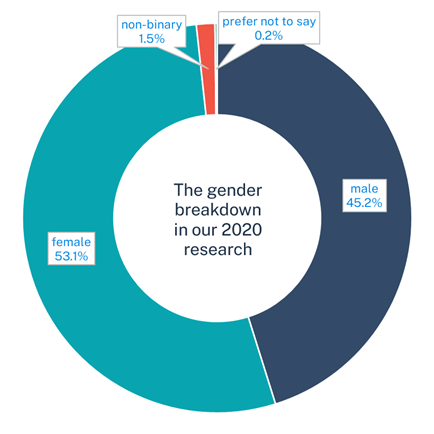

At the same time we conduct research with trainee lawyers to gather opinions on their careers in the context of their law firms. In 2020 we gathered opinions from 2,655 trainee lawyers. We then split the responses by gender and compare how the opinions differ and to what degree.

With this combined data we analyse key metrics: recruitment; retention; promotion and pay. We explore the reason why trends occur.