Events of 2020 taught us we haven’t done enough to tackle structural racism. What should the legal profession take away from Black History Month this year?

Ayesha Hayat, November 2020

Here at Chambers & Partners, we had the pleasure of hearing from Leslie Thomas QC of Garden Court Chambers and Alexandra Wilson of 5SAH Chambers for our Black History Month event. These two prominent members of the Bar offered their own unique perspectives on the importance of this cultural event and its wider context, then turned their focus to what the legal profession must do to become more inclusive for Black lawyers. This year own research revealed the true state of BAME recruiting and promotion in the UK legal market: the lacklustre results echo what we heard from our guest speakers, as you will see.

“Hearing the cry for help, Pearl’s parents made the decision to send her to a strange and foreign land to make a better life for herself,” tells Leslie Thomas QC, explaining where his roots lie through his mother’s past. “My mother followed a path like many immigrants who were escaping from former British colonies with the dream of making their own fortune on London’s streets, which were supposedly paved with gold.” Thomas tells a story familiar to the millions of second-generation children born in this country. The reality was far different from what Pearl and her parents had imagined. To find decent housing as an immigrant during post-war Britain in the 50s and 60s wasn’t a walk in the park, explains Thomas. “No Irish, No Blacks, No Dogs. Signs like these were commonplace in the UK. This was a time when the UK didn’t have proper anti-discrimination laws in place.” Fast forward to 2020, and we now have anti-discrimination laws, Black History Month has been adopted by the corporate world, diversity & inclusion dialogue is the norm, and there’s unconscious bias training being rolled out left, right and centre. So, we’ve solved the issue…right? The brutality of 2020 taught us that we are nowhere close.

From the disproportionate impact of the Covid-19 on the Black community, to the shocking murders of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and Ahmaud Arbery, the injustices the Black community face on a daily basis hit home. Black Lives Matter protests rose up around the globe with renewed vigour. These events resonated more profoundly with the world, sparking a new imperative among individuals and organisations to educate ourselves about Black history and culture. We learnt that we needed to do better.

“It’s been an extraordinary time in terms of the effects of what happened in the US but also how this has translated across our global network.”

The BLM movement prompted law firms to initiate conversations in the workplace with their Black colleagues on how they can improve diversity efforts in both the recruitment and retention of individuals from ethnic minority backgrounds. Graduate recruitment partner James Partridge of Allen & Overy tells us: “the first seater trainees got together and had a virtual discussion about the resurgence of the BLM movement and have shared some suggestions with me on what they think we should be doing from both a recruitment and retention perspective.”

Here we group different law firm types and the % of BAME trainees they hired for the past five recruiting cycles.

Our research shows an increase in BAME recruiting across the UK market this year, with the magic circle leading the way – evidence that these firms are listening and their initiatives can make an impact. This is happening, however, after a few years of shrinking numbers.

Partridge elaborates: “Externally, we will be working alongside Aspiring Solicitors on a Black Lawyer Mentoring Scheme. We are also working on a revamped Inclusivity Series for the next recruitment cycle, to give students and graduates an insight into the inclusive culture at the firm. As well as signing up to the Race Charter with Rare Recruitment. Internally we have also rolled out mentoring to all the BAME employees which has been extended to current and future trainees. It’s been an extraordinary time in terms of the effects of what happened in the US but also how this has translated across our global network.”

Our research shows that law firms vary in how effective their D&I initiatives are: some are window dressing; other deliver results. But Leslie Thomas QC mentions how “it’s all well and good having these discussions and having an equality statement, but there hasn’t actually been any significant movement in the advancement of black and other ethnic minority groups in the legal sector in the last 20 years. All it takes to come to that conclusion is to look at the ethnic minority figures in the judiciary.” The MoJ judicial diversity statistics report 2020 says just 7% of court judges were BAME, with Black judges making less than 1%.

Our research shows a flatlining in progress for BAME solicitors since 2015.

The availability of BAME role models is one major problem in the law. Creating them is the challenge for firms, agrees Partridge: “The bigger thing is much more around inclusion and retention and making sure that when people are in the business, they feel comfortable.” Our 2020 research shows BAME trainees are more likely to leave the firm in search of better D&I initiatives than their white peers.

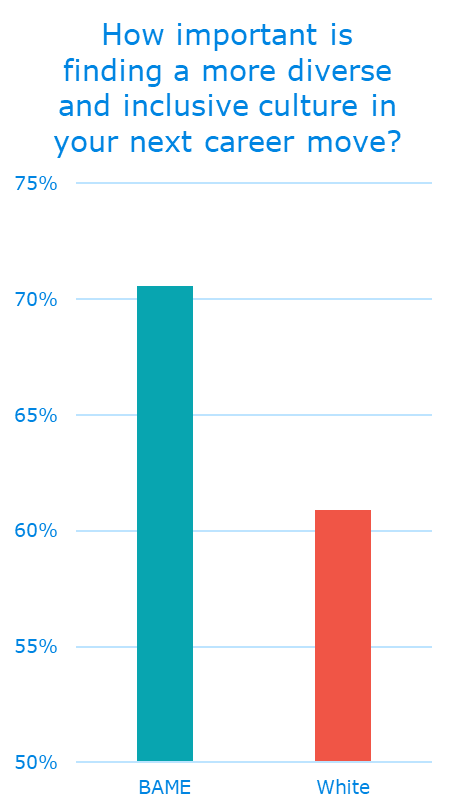

This graph shows the views of 2,655 trainees. It echoes Partridge’s point on the need to improve the firm’s environment itself to avoid high attrition rates of diverse talent.

This graph shows the views of 2,655 trainees. It echoes Partridge’s point on the need to improve the firm’s environment itself to avoid high attrition rates of diverse talent.

“There needs to be a culture shift,” said Alexandra Wilson at our BHM event. “Rather than highlighting the one Black individual in a cohort and viewing them as a token, we need to make them feel included in the day to day work. They’re already fighting an uphill battle.” HR teams and law firm management largely acknowledge this and would reject the notion that they are guilty of the degree of complacency that Wilson highlights. So if firms believe they have robust D&I policies and initiatives in place, what’s going wrong?

“It isn’t good enough to be an ally who believes they aren’t a racist since they aren’t overtly racist, using slurs and what not.”

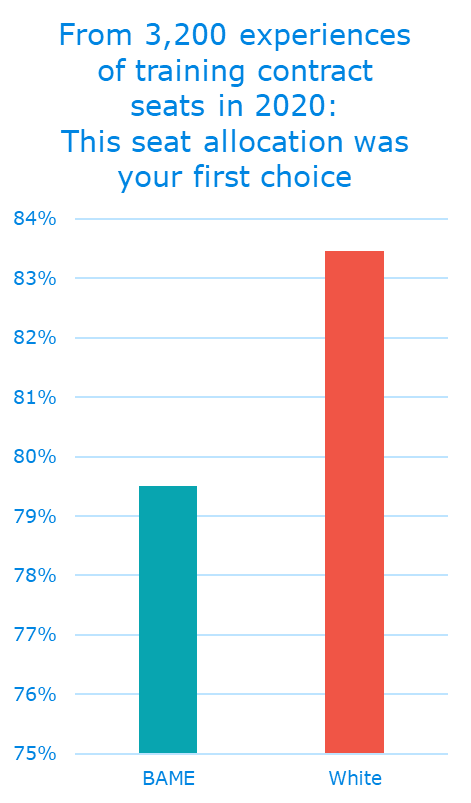

In this graph below we see 3,200 trainees telling us how likely it was that they got their first choice seat. BAME trainees were 4% less

In this graph below we see 3,200 trainees telling us how likely it was that they got their first choice seat. BAME trainees were 4% less  satisfied than their white peers. What we’re looking at here is implicit bias in action. Over the course of a career, these 4% disadvantages will accumulate, career paths will slowly digress, eventually causing BAME lawyers to lose faith in their law firms and find an employer who gets it.

satisfied than their white peers. What we’re looking at here is implicit bias in action. Over the course of a career, these 4% disadvantages will accumulate, career paths will slowly digress, eventually causing BAME lawyers to lose faith in their law firms and find an employer who gets it.

At our BHM event, Alexandra Wilson shared her thoughts on unconscious bias training: “In order for this to work, we need organisations to take it seriously, rather than seeing it as a tick-box exercise. We also need people to deter from using the term as an excuse. It isn’t good enough to be an ally who believes they aren’t a racist since they aren’t overtly racist, using slurs and what not. We need to be anti-racist. There’s no room for neutrality. We need to actively identify racism in the workplace, in our relationship with colleagues and clients and act against it. Only then will we be able to dismantle it.”

To BAME or not to BAME?

A large part of improving D&I involves language: it evolves quickly as research and events progress, and we have a duty to keep up. In this article and elsewhere, we default to the term BAME, but Alexandra Wilson asserts: “To use the term BAME is to essentially lump all the ethnic minorities together and to assume that they all share a similar experience and come from the same background.” Wilson also draws on the MoJ’s 7% BAME figure in the judiciary, with less than 1% being Black, and highlights that “there’s great disparity there.” The report, however, also recognises that due to the small numbers involved, the terminology of BAME was necessary to avoid any risk of disclosure of identity. So the term BAME serves a purpose perhaps in a statistical sense, but our research into law firm diversity shows it’s possible to hide behind the term and avoid scrutiny. And there isn’t a whole lot of clarity in where white minority ethnic groups fall within this, including minority groups such as Gypsy, Roma and Traveller of Irish Heritage groups, which of course marginalises these people further.

Where from here?

To consider how far we have come since Leslie Thomas QC’s mother arrived here is perhaps the wrong way to look at this problem: it makes us complacent, and 2020’s tragedies and heartache have taught us we are guilty of exactly this. Whatever we have all done, it wasn’t enough. This year has reminded us that we have a duty to educate ourselves, to empathise with the daily injustices the Black community faces, and to consider what our roles should be. But by shining a light on the achievements of the Black community and their pivotal role in our collective past and present, we naturally find cause to celebrate, we build cultural understanding and a shared future. Our five-year study of ethnicity in the law shows the year-on-year effect of not extending the message of Black History Month beyond October. The pressure is on the legal profession now not just to achieve those diversity targets, but at the same time to create an inclusive environment that – one day – removes the need to even have quotas and targets, or for us to have to track D&I stats.